|

|

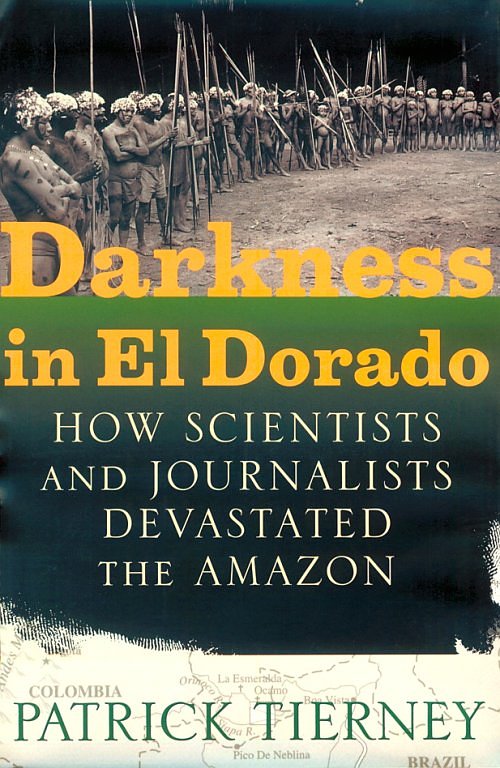

DARKNESS IN EL DORADO How Scientists and Journalists Devastated the Amazon Patrick Tierney W.W. Norton & Company, 2000, 431 pp. |

|

|

TieDark 03-2-20 |

||

Tierney, described only as a visiting scholar at the University of Pittsburgh, spent 11 years writing this book. It is a research document (50 pages of end notes) and expose about the impact of anthropologists, geneticists and journalists investigating the Yanomami people of the Amazon Rainforest of Venezuela. Tierney raises the issues of “physical suffering and cultural deracination endured by the Yanomami, brought on by expeditions that spread disease, warfare, and cultural chaos among one of the most vulnerable groups in the world.” (327)

Several years ago, I was fascinated by Mark Ritchie’s book, Spirit

of the Rainforest. Largely through

interviews with Yanomami’s, and evangelical missionaries, Ritchie described the

power of the spirit world over the Yanomami.

He bitterly attacked anthropologists who had worked in the area. Because anthropologists are often openly

critical of missionaries, I was interested to read Tierney’s perspective.

Tierney has spent much time researching this book, both

among the people of the Amazon and in the written records, archives, and film

footage. His research indicates that

the “normal” anthropologists caused all kinds of illness and wars among the

people and did little to help them, that they misrepresented their data to make

it conform to their theories, and that the “abnormal” anthropologists were

almost unspeakable.

I found Tierney very believable until he got to the chapter

describing research done on behalf of the Atomic Energy Commission. The introduction (in an area in which I have

some professional background) was so one-sided as to call into question the

objectivity of the remainder of the book.

Napoleon Chagnon, a primary character in the book, published

Yanomamo: The Fierce People, in 1968.

It became the all-time best seller in anthropology, purchased by 4

million students. (7) Tierney was surprised to find the terrifying

and ‘burly’ people were “among the tiniest, scrawniest people in the world,”

adults averaging four feet seven inches in height. (8)

Chagnon’s book surpassed Coming of Age in Samoa by

Margaret Meade, who “conjured up an idyllic society in the South pacific, whose

sexual freedom coincided with the theories of her mentor….” “Mead managed to ignore the fact that the

Samoans had one of the highest indices of violent rape on the planet.” (11-12)

Chagnon arrived at the Amazon-Orinoco watersheds in

1964. “Chagnon picked up where Social

Darwinists left off. He emphasized the

necessity of lethal competition in nature and the inevitable dominance of murderous

men in a prehistoric society.” (12)

The films made by Chagnon, and aired many times by Nova and

the BBC, for example “Warriors of the Amazon,” followed “a pattern of

choreographed violence….” “In reality,

the hosts had not had any wars in years, until the film crew arrived….” (14)

“Anthropolotists have left an indelible imprint upon the

Yanomami. In fact, the word anthro

has entered the Indians’ vocabulary, and it is not a term of endearment. For the Indians, anthro has come to

signify … a powerful nonhuman with deeply disturbed tendencies and wild

eccentricities….” (14)

“Chagnon, according to videotaped testimony… played the role

of a shaman who took hallucinogens and incorporated the most fearsome entities

of the Yanomami’s sprit pantheon.” (15)

“Villages were named for Lizot and Chagnon, as though they

were great Yanomomi chiefs. And the

anthropologists’ village took on their personalities. Chagnon’s Yanomami were more warlike than any other group;

Lizot’s village became the capital of homosexuality.” (15-16)

The ability to bring epidemics “… is unquestionably the most

impressive legacy of scientists and journalists on the Upper Orinoco. …hundreds of Yanomami died in the immediate

wake of exploration and filming. (16)

Ch 3 is about Chagnon filming The Feast, and other

wars. The chapter describes how Chagnon

provoked the wars he filmed. “Within

three months of Chagnon’s sole arrival on the scene, three different wars had

broken out, all between groups who had been at peace for some time and all of

whom wanted a claim on Chagnon’s steel goods.”

(30)

Ch 4 discusses

Atomic Energy Commission collection of a multitude of blood samples for genetic

study of a control group to contrast to the Japanese exposed to the atomic

bomb. Among other problems, the

Yanomami experienced epidemics of infections disease as a result of the

contact. (51)

Ch 5 describes how genetic experiments of measles

vaccinations with a live vaccine in 1968 resulted in hundreds dieing of the

imported disease. It appears the

investigators did not make serious efforts to get doctors or medicines for the

dieing people.

Ch 6 described what really happened in filming. It was all staged and the Indians did it for

the gifts.

Ch 7 describes how exaggeration, imagination, and invention twisted facts to satisfy scientific curiosity. These were not first contacts with pristine societies. The presumed peace brokering was actually causing war that would not otherwise have happened. Gun killings were blamed on missionaries loaning guns when they were obtained by trading goods they got from payment by Chagnon for the filming. Imaginative theories were reported as facts. “Students who see The Ax Fight, Magical Death, or any of the twenty other films about the Mishimishimabowei-teri have not been burdened by the knowledge that the community was decimated shortly after the filmmaking.” (120)

Ch 8 follows the French anthropologist Jacques Lizot, a

Gypsy, homosexual, and Parisian. He

“established a reputation for both ferocity and erotic energy that surpassed

any Yanomami’s.” He was repeatedly

denounced for child molesting.

(126) He was a protégée of

Levi-Strauss who “firmly eschewed activism on their behalf because it would

have shattered his scientific mirror of contemplation and objectivity.” (127)

“Lizot traveled in the company of boys, who began

accumulating trade surpluses.”

(127) Stories about his

pedophilia were commonly known. When

Lizot wrote the ethnography of Yanomani sexuality, he reported that sodomy was

normal for children. According to

Lizot, there was no shame and no blame for any kind of sexuality. (133)

(According to others, homosexuality was rare and never open.) In some villages, sodomy became Lizot-mou,

“to do like Lizot.” (134)

“Everybody was getting all sorts of gifts.” “We used to call it Boys Town. They all had perfume and whole necklaces and stereo equipment they’d listen to. It was wild. It was obvious what was going on.” (143) “Many people had tried to remove Lizot and failed. Many people had tried to stop Lizot. No one had gained health or good fortune from it.” (147)

Ch 9 is about Charles Brewer Carias, another of the big men

involved among the Indians. He was a

research associate of the New York Botanical Garden, a photographer, and sort

of a wild man. He got involved in the

mining business.

Ch 10 describes how the anthropologists promoted their

Darwinian theories that the men who killed the most got the most wives and had

the most progeny, even though the real data didn’t support it. Chagnon created the popular image of

Yanomami waging war for women. He

didn’t seem to be aware that he wasn’t accurately representing the data. (178)

In Ch 11, a mistress of the Venezuelen president gets into

the act by financing some combination of nature center and illegal mining

operation.

A number of times in the book it comes up that people were

dying during the filming and the anthropologist would not summon help for

them. Here’s one example: “And I went up to Chagnon and said, ‘You

know these people are really sick. Some

of them could die. We’ve been in one

village where three people died within twenty-four hours. Here people are spitting blood. I think we should go and get help.’ There

were doctors at the mission. There was

medical help that could be gotten just a few hours away. And Chagnon just told me that I would never

be a scientist. A scientist doesn’t

think about such things.” … “But he said, ‘No. No. That’s not our problem.

We didn’t come to save the Indians.

We came to study them.’” (184)

“Chagnon and Brewer knew how to attract the interest of the

international press corps—by providing helicopter rides to virgin

villages.” (187) The press doesn’t come off very good in this

book either – willing to risk the lives of the Yamomami for a breaking story,

and not digging too carefully into facts.

Ch 12 gets more into the illegal gold mining operations and

the havoc caused among the Indians. Ch

13 is more about the staging and results of filming. These are portrayed as first time western contacts. “In the film, new trade goods could be seen

all over the freshly constructed shabono (pots without smoke in them,

shiny machetes and axes.)” (217) It was clear the Yanomami had been paid for

the acting, and had also suffered much.

A family of American missionaries, the Dawsons, watched Warriors

of the Amazon. Among their eight

members, they had collectively spent over 200 years with the Yanomami and had

contact with every linguistic group except one. “The missionaries stopped laughing when the camera followed the

progressive weakening and death of a mother and her newborn infant, which

occurred over the weeks the film crew was in the village. ‘In most cases, death from fever is a very

preventable death,’ said Mike Dawson, who has lived since birth with the

Indians, over forty-five years. ‘With

just a little bit of help, they could have pulled through. The film crew interfered in every other

aspect of their lives. Let’s be

real. They’re giving them machetes,

cooking pots, but they can’t give a dying woman aspirin to bring her fever

down?’” (216-17)

“What they paid for filming her funeral must have been

enormous,” said Mike Dawson. “I mean,

they’ve never let us film a funeral, and we’ve been with them all these years. Believe me, a lot of lives could have been

saved for what they paid to get that film.”

(218)

“There is not one instance where the film was not staged, in

my experience.” Father Jose Bortoli,

head of the Salesian mission of Mavaca.

(219)

“Artistically, they repeated the oldest cliché in the

Yanomami film repertoire—a misleading film about a fake feast that co-generated

a dangerous new military alliance. And

it was all performed in the middle of a deadly outbreak of falciparum

malaria.” (220)

“The content of Warriors of the Amazon followed the

commercial requirements of television sequels—in this case, the never-ending

need to obtain supplies of savage, remote Indians.” “The role of the film crew was kept invisible even as it made the

ultimate decisions: to evacuate the sick or let them die.” (222)

Every single place that Chagnon claimed first contact and

discovery had been really achieved by Helena Valero, a Portugese girl captured

at age ten who had lived decades among the people. “In the history of discovery, accuracy mattered. In the history of Amazonian discovery,

Chagnon misrepresented Valero’s life.”

(246) “The scientific prestige

of The Fierce People, as well as the famous thesis that Yanomami

murderers have more offspring than nonmurderers, depends on the reliability of

oral histories. Yet Chagnon’s reports

diverged remarkably from Valero’s, a woman with a phenomenal memory of

clans. (247) If the anthropologists had given Valero due credit, it would have

detracted from their own mystique.

(248) Chagnon’s series editors

“have collaborated for thirty years in the theft of Helen Valero’s singular

achievements.” (249)

Ch. 16 deals with the diet and health of the people. Ch 17 deals with how the Yanomamo, who have

much involvement with the spirit world, interpret western technology such as

planes, helicopters, guns, flash cameras, etc.

“If there is one art at which the Yanomami excel any people

I have met, it is in the realm of the spirit.

When a man becomes a shaburi, he fasts on a liquid plantain soup,

while participating in marathon chanting and hallucinogenic drug taking, all

under the direction of older healers.”

“…animal skins represent spirits that the young shaman will welcome into

his chest. The jaguar is a powerful noreshi,

alter ego, which many shamans incorporate.

Some shamans have more than one such spirit.” “In a mysterious way, the Yanomami consider themselves to be

animal spirits (noreshi), nature spirits (hekura), and humans,

all at once.” “The Yanomami are very

confident of their knowledge of the spirit world, as confident as they are of

our ignorance in that realm.” (285)

Ch 18 deals with radioisotope distribution studies done on

the Yanomami’s, sponsored by the Atomic Energy Commission. The introduction about the AEC is so

negatively and bitterly biased, from a current popular university political

view of the atomic bomb, that it casts questions about the possible political

motivation of the whole book. One

wonders if the postmodernists are correct: everyone writes to persuade others

of their view and sees and interprets all the data from their own biased

perspective.

Consider this sentence:

“Colonel Stafford Warren [chief of the Manhatten Project] and his kin

were the real unokais [murderers], who had killed 150,000 people, the

great majority unarmed civilians, in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” (313) ************